The Design Thinking Process…Optimized for B2B

If you develop new products, the design thinking process can help. All the more so if you’re a B2B innovator: You can upgrade the most important parts of design-thinking in ways consumer goods developers can only wish for. Here’s what you must do differently for B2B-optimized design thinking.

Imagine a chemical engineering student taking an exam on energy transfer. Some years later, she is sizing a heat exchanger for her company’s plant expansion. As with her college exams, the problem is well-defined: This much mass at a given flow rate must be heated to that temperature. We call these “tame” problems.

Now picture an urban planner designing housing for the disenfranchised. He needs to consider affordability, aesthetics, employment mobility, sustainability, economic development and more. Ill-defined challenges such as these are called “wicked” problems. Increasingly, the design thinking process is being used to solve them.

The concept of design thinking was first introduced by Nobel Prize laureate Herbert A. Simon in his 1969 book, The Sciences of the Artificial. Peter Rowe’s 1987 book, Design Thinking, popularized the term, as he described approaches used by architects and urban planners. David Kelley, the founder of IDEO, first applied the design thinking process to business opportunities.

The design thinking process is indeed well-suited to the business world, especially in new product development—the focus of this article. Why? When a chemist or engineer goes into the lab to develop a product, they’re usually treating a wicked problem as though it were a tame problem. Their solution fails to please users because they never understood those users’ needs. Design thinking can fix this.

They’re usually treating a wicked problem as though it were a tame problem.

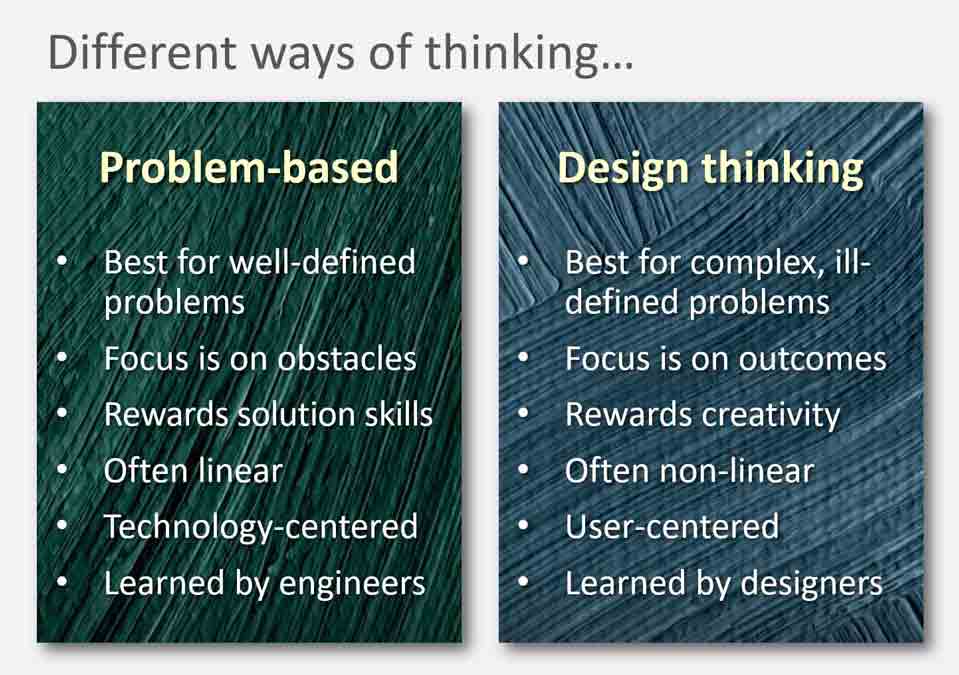

The design thinking process—also referred to as “user-centered design”—differs from the analytical, scientific method most technical people are trained in. Instead of starting with the problem to be solved, you begin the design thinking process by creating a picture of a desired future state. John Chris Jones, author of Design Method, framed it in terms of timing:

Both artists and scientists operate on the physical world as it exists in the present… while mathematicians operate on abstract relationships that are independent of historical time. Designers, on the other hand, are forever bound to treat as real that which exists only in the imagined future and have to specify ways in which the foreseen thing can be made to exist. (Italics added)

Many find the design thinking process difficult to apply, especially if they were handed one well-defined problem after another in their college years. We’ll begin by exploring how design thinking is typically applied today. Then we’ll present a roadmap you can use for a B2B-optimized design thinking process. In other words, we’ll help you tame the process of solving untamed B2B problems. We’ll do so by covering these topics:

- How the design thinking process works: The 5 steps of design thinking

- Benefits of the design thinking process: Why companies are turning to this

- The B2B design paradox: B2B challenges and advantages vs. B2C

- Optimizing design thinking process Step 1: How to “Empathize” better in B2B

- Optimizing design thinking process Step 2: How to “Define” better in B2B

We’ll help you tame the process of solving untamed B2B problems.

1. How the design thinking process works

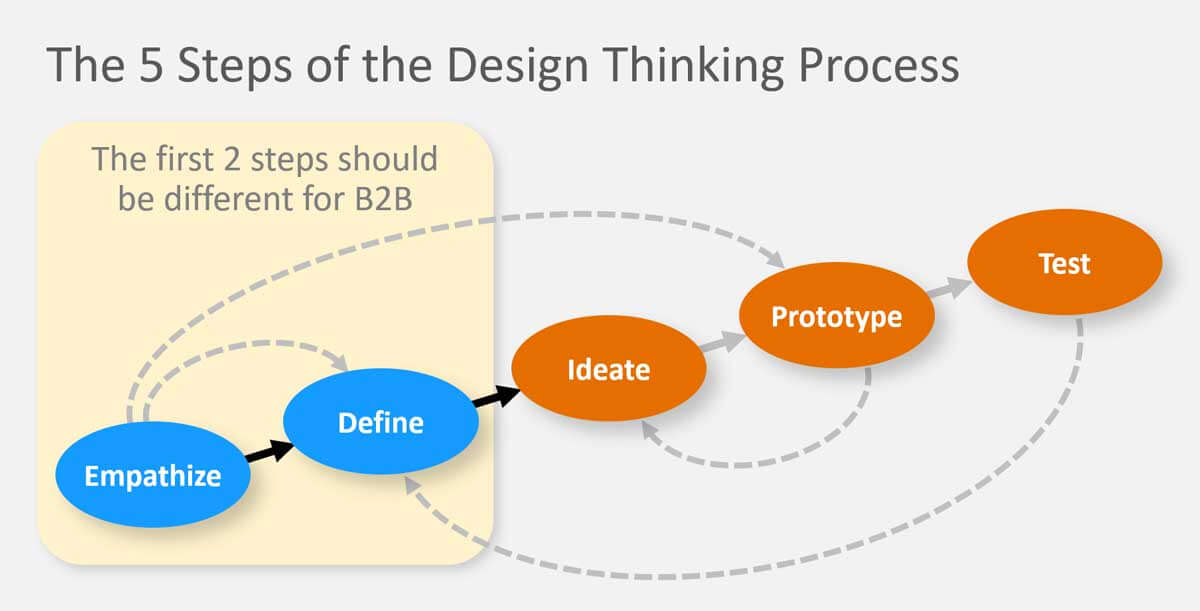

The Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford uses five-stages to describe the design thinking process. In practice, these steps aren’t always sequential, as teams may operate them out of order, in parallel, or repeat them.

Later, we’ll explore why the first two steps should be quite different for B2B. For now, here’s how most users deploy the design thinking process:

Empathize: This is where you research your users’ needs. You seek to develop an empathetic understanding of their world and their needs. You set aside your own biases, assumptions, and pre-conceived notions and try to “think like the user.” For many, this is the most challenging part of the design-thinking process. After all, in school thinking like the user “wasn’t on the test.”

Define: You gather together everything you’ve learned and analyze your observations. You synthesize these into well-defined “problem statements.” This is key: According to Charles Kettering, “a problem well stated is half solved.” The design thinking process typically suggests you create personas—fictional characters to represent different types of users—to keep your efforts user-centered as you move to the next step.

Ideation: A common form of ideation is the brainstorming session: Your team generates many possible solutions, building off each other and withholding judgment. You may use trigger methods to think “out of the box” in this divergent phase. Then you develop selection criteria and converge on the most attractive solution(s).

In school, thinking like the user “wasn’t on the test.”

Prototype: Next you enter the experimental phase. You create a simple, early version of your solution(s) to test. This could be a simple concept drawing or an inexpensive, scaled down model of your solution. In Lean Start-up methodology, this is called a Minimum Viable Product.

Test: Now you put your prototype in front of users to see how they interact with it. The design thinking process involves more than asking for verbal feedback. You also observe users and try to pinpoint any design flaws. You might need to create fresh iterations, return to an earlier step, or even address new problems you just uncovered.

2. Benefits of the design thinking process

A five-year McKinsey study found companies most strongly committed to design principles had 32% more revenue and 56% more total returns to shareholders. These companies shared common practices, e.g. putting the user first, embedding designers in teams, and tracking customer usability metrics. These financial results aren’t surprising when you consider the following benefits of the design thinking process:

- Stronger value propositions: Research by the AIM Institute has shown the most important driver of organic growth is delivering a strong value proposition in new products. Yet most companies start with theirideas, not the needs of their customers. The design thinking process corrects this.

- Rapid customer insight: Some companies take a year or two to develop a new product, get disappointing sales results, and then try another new product. That’s far too slow for learning customer needs. Better to iterate around customer needs within a single new product effort, using the design thinking process.

- Customer engagement: Customers love being asked about their needs… especially by professionals who are truly interested in their answers and intend to act on them. This is particularly powerful for B2B firms applying the design thinking process to single large accounts or markets with just a few customers.

- Transformational innovation: Many companies are mired in incremental innovation as they try to improve existing products and services. With the design thinking process, teams “step back” to holistically look at the entire user experience. This often leads to exciting, new-to-the-world innovation.

- Less squandered R&D: Many companies invest millions of R&D dollars developing “cures for no known diseases.” Massive resources are misspent because they were not properly “aimed” at the right design targets. A customer-empathetic design thinking process corrects this.

- Reduced commercial risk: With the design thinking process, only real customer needs are pursued, so commercial risk—the leading cause of new product failure—plummets. This lets R&D do what it does best: resolve technical risk.

- Functional silos eroded: The design thinking process promotes the use of highly-collaborative, multi-functional teams. This not only promotes more effective work within a project team, it erodes the functional silos that plague organizations well after project completion.

While hard to measure, one of the greatest benefits of a design thinking process is its impact on a business’s collective mindset. Peter Drucker said, “culture eats strategy for breakfast.” A design thinking process promotes a cultural shift from “inside-out” to “outside-in.” As more members of your organization practice a user-first mentality, you’ll see benefits that are hard to track but highly impactful.

3. The B2B design paradox

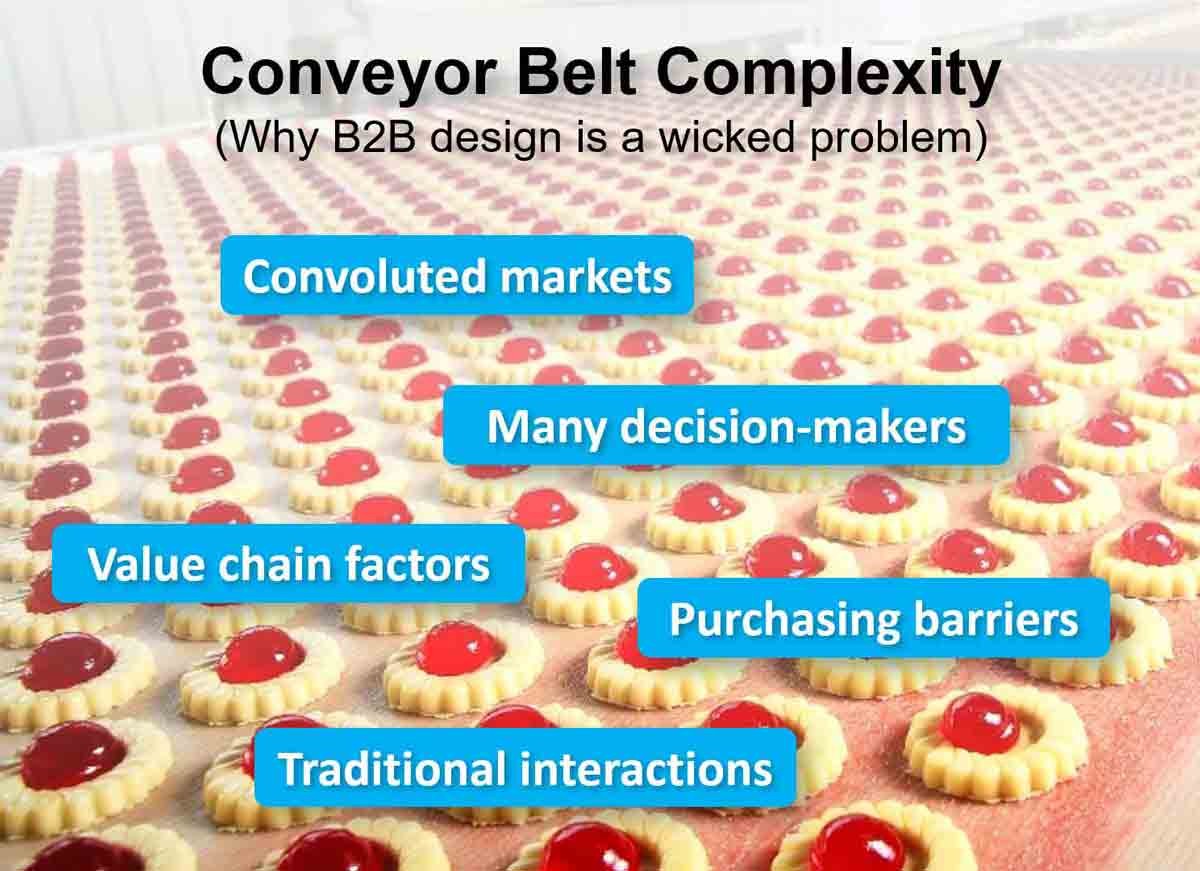

Compared to B2C, B2B companies face greater design challenges… but also enjoy greater advantages. To understand these challenges and advantages within the design thinking process, consider two case: In the B2C case, you produce men’s dress belts, and in the B2B case you produce conveyor belts used in food production.

B2B design paradox: B2B companies face greater challenges… but also enjoy greater advantages.

Let’s begin with the B2B challenges. The B2B producer of conveyor belts faces much more complexity in understanding customer needs. The B2B design problem is “wicked” for several reasons:

- Convoluted markets: Compared to men’s dress belts, targeting the right conveyor belt market segment is tricky. Should you develop the same belt for baking cookies as for pizzas? Are in-store baking and factory baking needs the same? Should you segment by type of food… size of the tunnel oven… something else?

- Many decision-makers: It’s common to have several people influencing and making B2B buying decisions. For food conveyor belts, this might include a production supervisor, maintenance foreman, process engineer, purchasing agent, and more. Should you interview them separately or at the same time? Who should you most try to please?

- Value chain factors: You sell your conveyor belts to manufacturers of commercial conveyor ovens. To understand the most important user needs, you must “leapfrog” these direct customers and interview their customers: the baked goods producers that use these ovens. But you don’t have any prior relationship with them. And will interviewing them upset your direct customers?

- Purchasing barriers: When you try to speak to an engineer or production person, their purchasing agent may block it. These sourcing professionals are often interested in one thing: lower price. If they limit other conversations you have within their company, can you get around them? Should you?

- Traditional interactions: When B2B suppliers and customers meet, the latter have come to expect a one-way flow of information. It’s from the supplier’s salesperson selling or technical service rep solving. They no longer expect you to ask about their needs in any meaningful way. How do you break these old habits?

These challenges make B2B innovation a wicked problem. But they also make it ripe for a better approach: the design thinking process. Fortunately, there are also substantial B2B advantages over B2C.

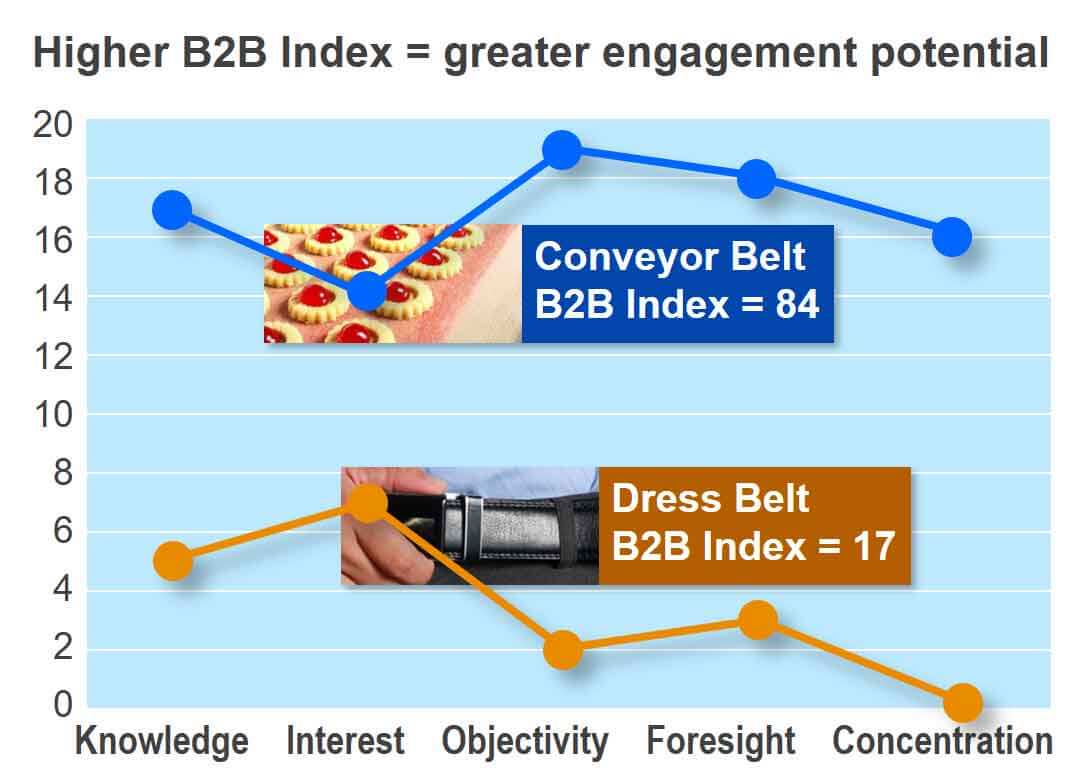

To understand these advantages, imagine interviewing a food processing engineer about conveyor belts, and a businessman about dress belts. Sure, the conversations would be different, but how and why? Consider five advantages—all relevant to the design thinking process—that you would enjoy in the B2B interview.

Knowledge: The engineer knows a lot about belt requirements—operating speed, disinfection procedures, maintenance schedule, etc. You’ll learn more from the engineer than the dress belt buyer for two reasons: The engineer had more training on this topic, and spends more time thinking about this topic.

Interest: Who will be more willing to meet with you? The engineer, because you could make him a hero at work. Your innovations could deliver financial benefits from increased processing speed or reduced downtime. How interested is the dress belt buyer? Here’s a clue: You have to pay him to join your focus group.

Objectivity: We reject the notion that emotion is absent in B2B decisions: The passion for innovation and achievement can run high with business customers. But B2B emotion is grounded in objectivity, not divorced from it. The food processing engineer is one of several decision-makers, and is held accountable to policies, procedures, and superiors. His decision-making will be rational, stable, and understandable.

B2B emotion is grounded in objectivity, not divorced from it.

Foresight: The engineer might say, “If your belt operated at a lower tension without slippage, we could extend bearing life and cut maintenance costs.” Without seeing any prototype, he could predict likely benefits in a measurable fashion. The dress belt buyer might say, “Show me your belts and I’ll tell you which I like.”

Concentration: You can measure a market’s concentration by asking, “What percent of total demand comes from the 10 largest buyers?” The answer might be 80% for confectionary food belts, and far less than 1% for dress belt consumers. Just a handful of interviews in a concentrated B2B market can represent most of that market’s total buying power.

These advantages can help B2B companies understand customer needs better… the critical first step in a design thinking process. If your B2B customers are knowledgeable, they are able to help you design a new product. If interested, they are willing to do so. With objectivity and foresight, they can explain their decision-making and predict future needs. And in highly concentrated markets, you can directly interact with a large portion of the market’s buying power.

But a word of caution: The labels “B2B” and “B2C” can be blunt and imprecise. The AIM Institute has developed the B2B Index to measure “how B2B” any market is. The higher your Index, the more you can enjoy these B2B advantages in your design thinking process.

To determine your market’s B2B Index with a free online tool, visit www.B2BMarketView.com. The closer your B2B Index is to a maximum of 100, the greater your potential to engage with customers. This is perfect for the first step of the design thinking process… empathizing with the user.

4. Optimizing design thinking process Step 1 (Empathize)

Step 1 of the design thinking process is developing an empathetic understanding of the customer’s world and needs. It’s a major stumbling block for many B2B professionals. Most lack the skills and tools. Some don’t even think it can be done.

When I hear a B2B professional say, “But our customers can’t tell us what they want,” this analogy comes to mind: On their first date, a young man takes a woman to a cheap, noisy restaurant. Before the menus arrive, he leans forward and asks, “Will you marry me?” She won’t?! Well, obviously, she’s not the woman for him, right?

If you want to understand your customer’s deepest needs, you need to create the right environment. This is not a sales call with a purchasing agent who’s complaining about prices.

The right environment is not a sales call with a purchasing agent who’s complaining about prices.

Instead, conduct B2B-optimized Discovery interviews. Also conduct customer tours—aka, ethnographic research—but for high B2B Index markets, these interviews are your most transparent window into customer needs. After all, the people you interview have high knowledge, interest, objectivity, and foresight. They can explain their needs… if you know how to ask.

Since 2005, the AIM Institute has taught and refined an optimal environment for transferring what’s in B2B customers’ brains into your brain. These Discovery interviews allow you to take the first step of the design thinking process far beyond what’s possible in B2C. They look like this:

- Let customers see your notes. Display customers’ comments so they can make corrections and build off each other’s thoughts. This works very well in a web-conference, as described in the white paper, Virtual VOC.

- Use digital “sticky notes.” Thanks to years of brainstorming, these give customers a visual cue that says, “It’s up to you to generate ideas: We’re just here to record them.”

- Don’t use hired guns. There’s a time for engaging market research firms, but this isn’t it. You need to personally probe and understand subtleties. Bring your technical representative so customers know they’re talking to someone who can innovate for them.

- Interview multiple job functions. When several customer contacts are generating ideas in the same meeting, they build off each other’s ideas. You’ll learn a great deal from their interaction.

- Interview multiple companies. Meet with several companies (separately)… both direct customers and down the value chain. The greatest value you deliver may be for your customers’ customers.

- Drop the boring questionnaire. How excited are you when someone comes to your home asking you to answer their survey questions? Your busy customers have even less time for this nuisance while at work.

- Seek only customer outcomes. Ask them for any problems they have in their “job-to-be-done” you’re discussing. Then ask what they’d like in their “ideal world.” Never sell. Never solve. Just search.

- Let customers lead. After you hear, probe, and record an outcome on a sticky note, simply ask “What else?” This lets your customers generate the outcomes they care about.

- No “product concepts.” If you have a hypothesis, test it silently. Don’t mention it; just let customers volunteer desired outcomes. If their outcomes can be satisfied with your concept, you’re on the right track. Otherwise, you’re not.

- No prototypes. Save these for later. In general, do you prefer to talk about your cool ideas or someone else’s ideas? Your customers will be more engaged if these early conversations are about what’s important to them.

- Use “trigger maps.” You can spark fresh thinking by displaying one of these. A trends map, for instance, shows trends that could impact the customer’s future. This helps them generate additional desired outcomes.

- Skillfully listen & probe. Show your interest and learn more by recapping, appreciating silence, making affirming comments, and asking thoughtful, open-ended questions.

Some Discovery interviews have run over several hours because customers felt they owned the conversation. Besides learning more, you engage customers in your project. When you begin selling your new product later, you’ll have willing customers who were “primed” to evaluate and buy because of these interviews.

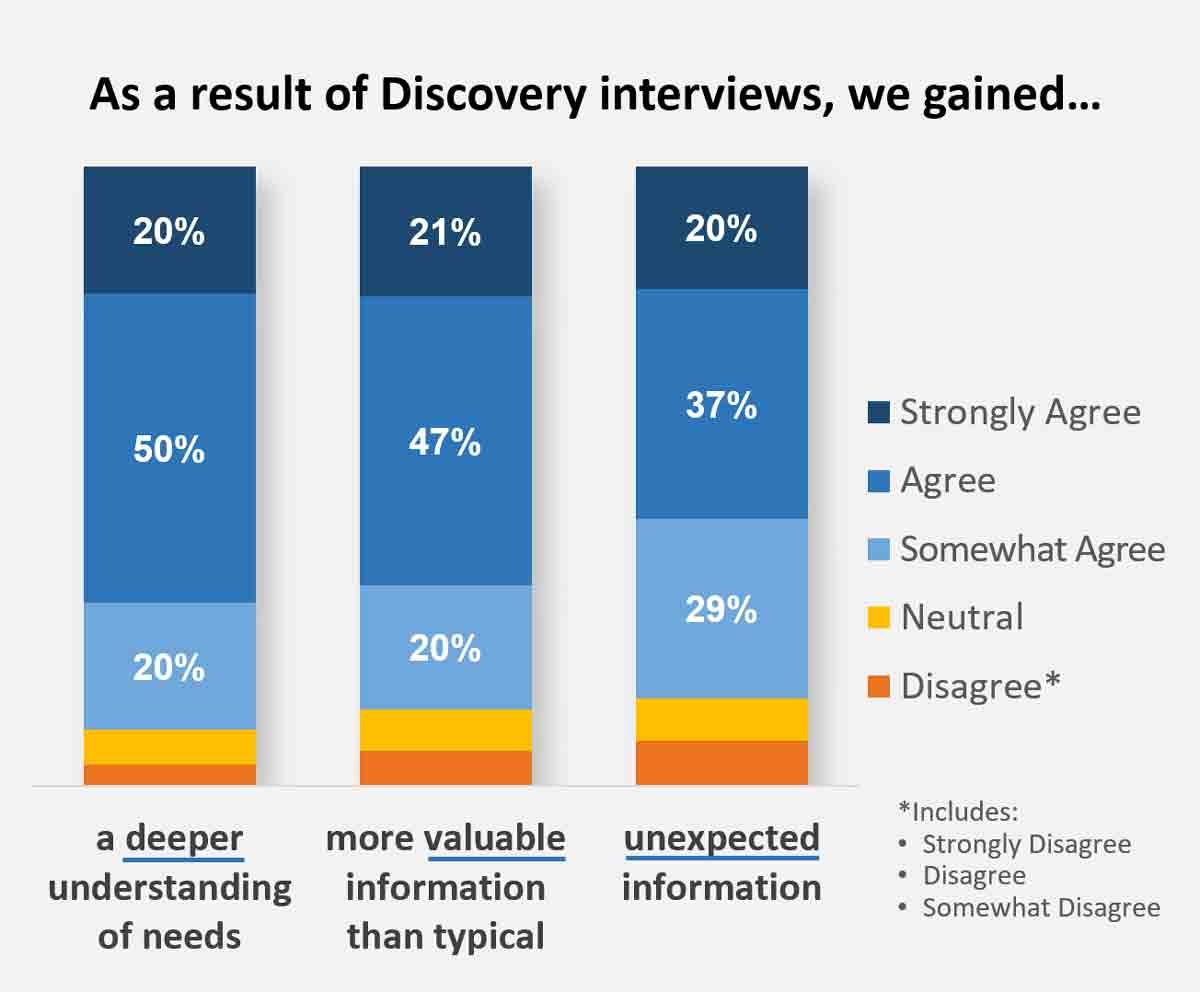

In this step of the design thinking process, you want to uncover otherwise unarticulated customer needs. Research shows Discovery interviews help. We surveyed 397 trained practitioners from 64 companies, who responded based on their experience in over 1800 Discovery interviews. 86-90% said their interviews helped them:

- Gain a deeper level of understanding of customer needs.

- Learn more valuable information than in typical customer interactions.

- Learn unexpected information.

Suppliers were understanding valuable customer information more deeply, and much of this was unexpected. This is exactly what we want from our first design thinking process step, “empathize.”

5. Optimizing design thinking process Step 2 (Define)

Step 2 is “defining” what needs you should satisfy with a new offering. In B2C application of the design thinking process, you may need to create “personas” of different types of users and then create problem statements to work on.

You’ll find this step is faster, easier, and more accurate for B2B. In Step 1, your Discovery interviews were qualitative and divergent, because you asked for more and more outcomes. In Step 2, you move to quantitative, convergent Preference interviews. You narrow your design targets to include only those outcomes important to customers that are currently unsatisfied—the only ones they might pay a premium to improve.

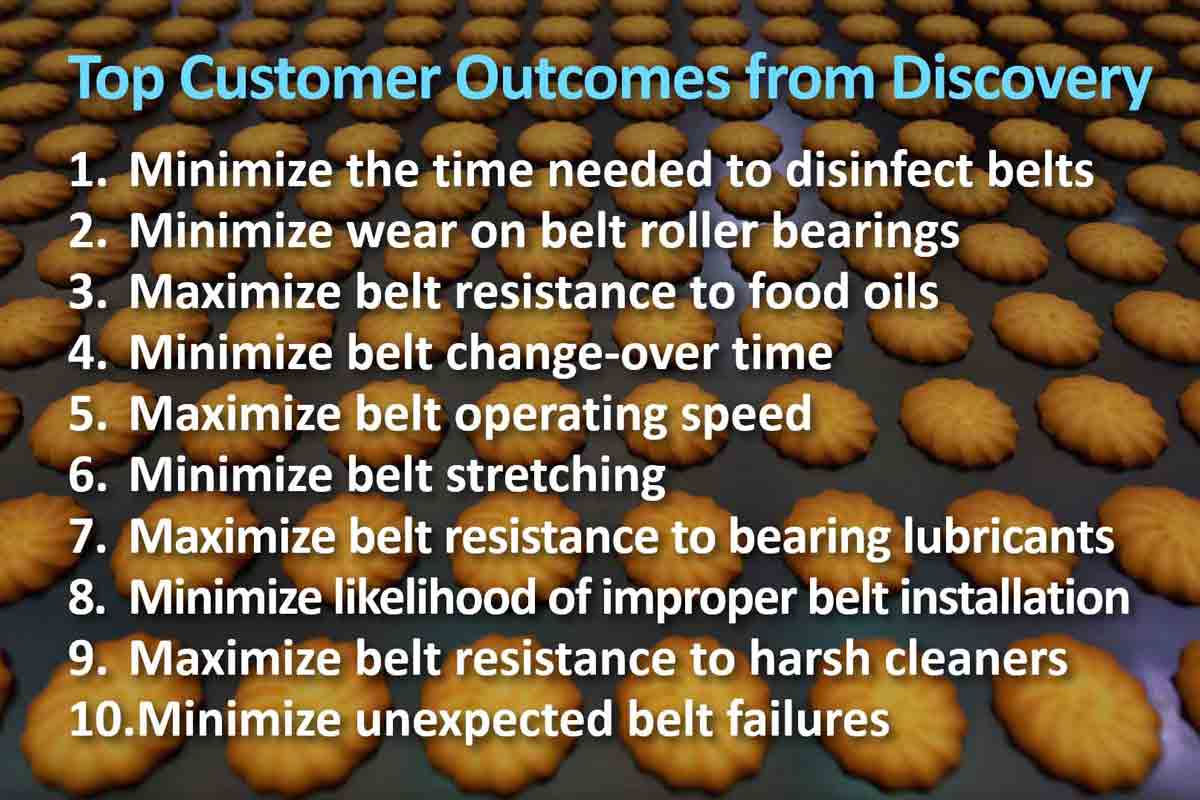

Imagine your team completed Discovery interviews on conveyor belts with several confectionary baked goods companies. These interviews generated dozens of desired customer outcomes. Your top ten are shown here.

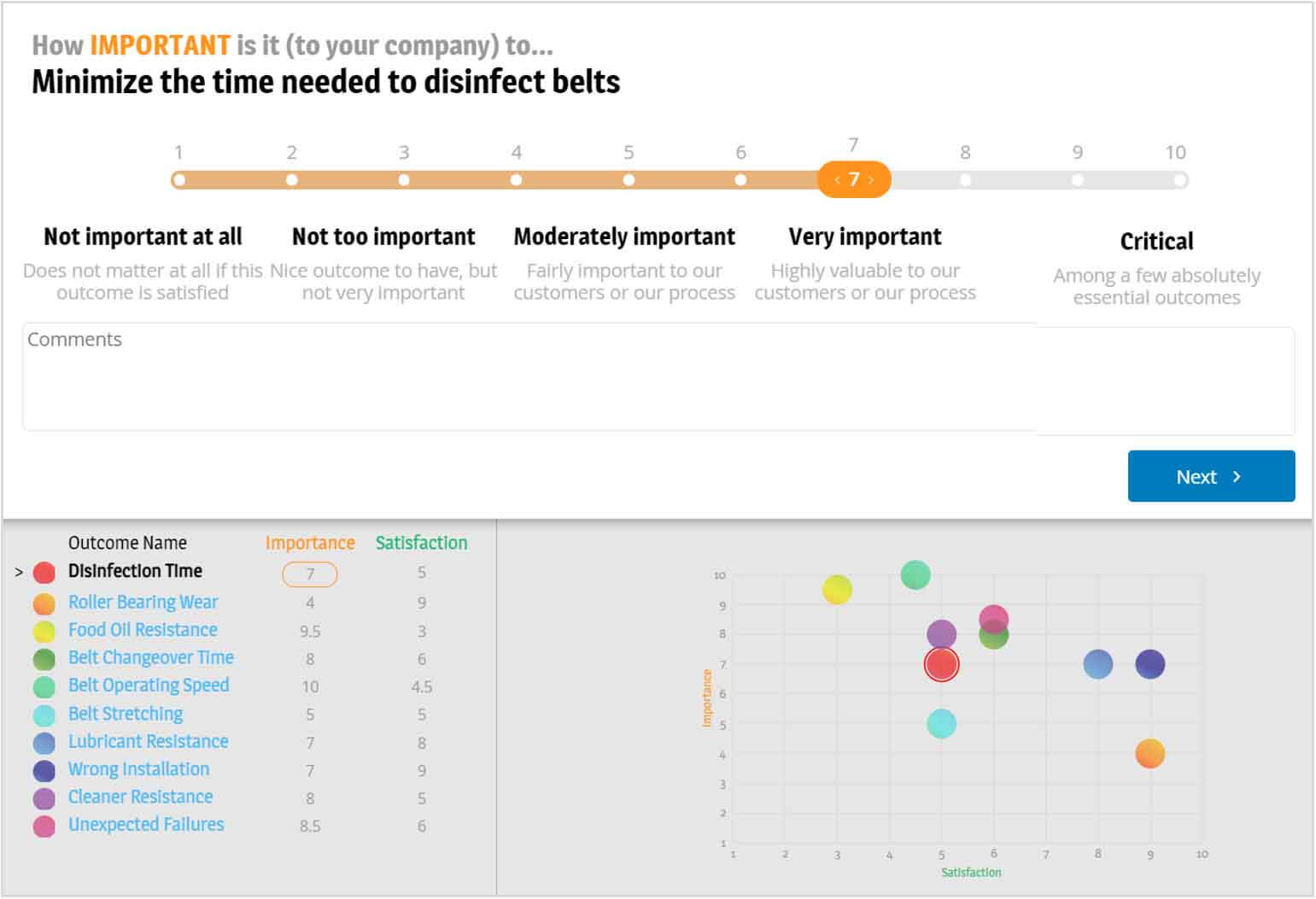

During quantitative Preference interviews, you ask two questions for each outcome: First, “How important is it to… (minimize the time needed to disinfect belts)?” Second, “How satisfied are you today with your ability to… (minimize the time needed to disinfect belts)?”

Make sure customer feedback is quantitative: The “language of math” ensures wishful thinking and confirmation bias won’t distort your understanding of their needs. The Blueprinting process uses 1-to-10 anchored scales. In the example below, the customers tell you how far to slide the rating scale.

Conduct your Preference interviews with all key decision-makers and decision-influencers at the same time. Disagreements are welcome. The market manager may not care how long it takes to disinfect a food belt, but the production supervisor does. If they can’t agree on a rating ask, “How important is belt disinfection time for your entire company?” After all, each department won’t be buying its own conveyor belts.

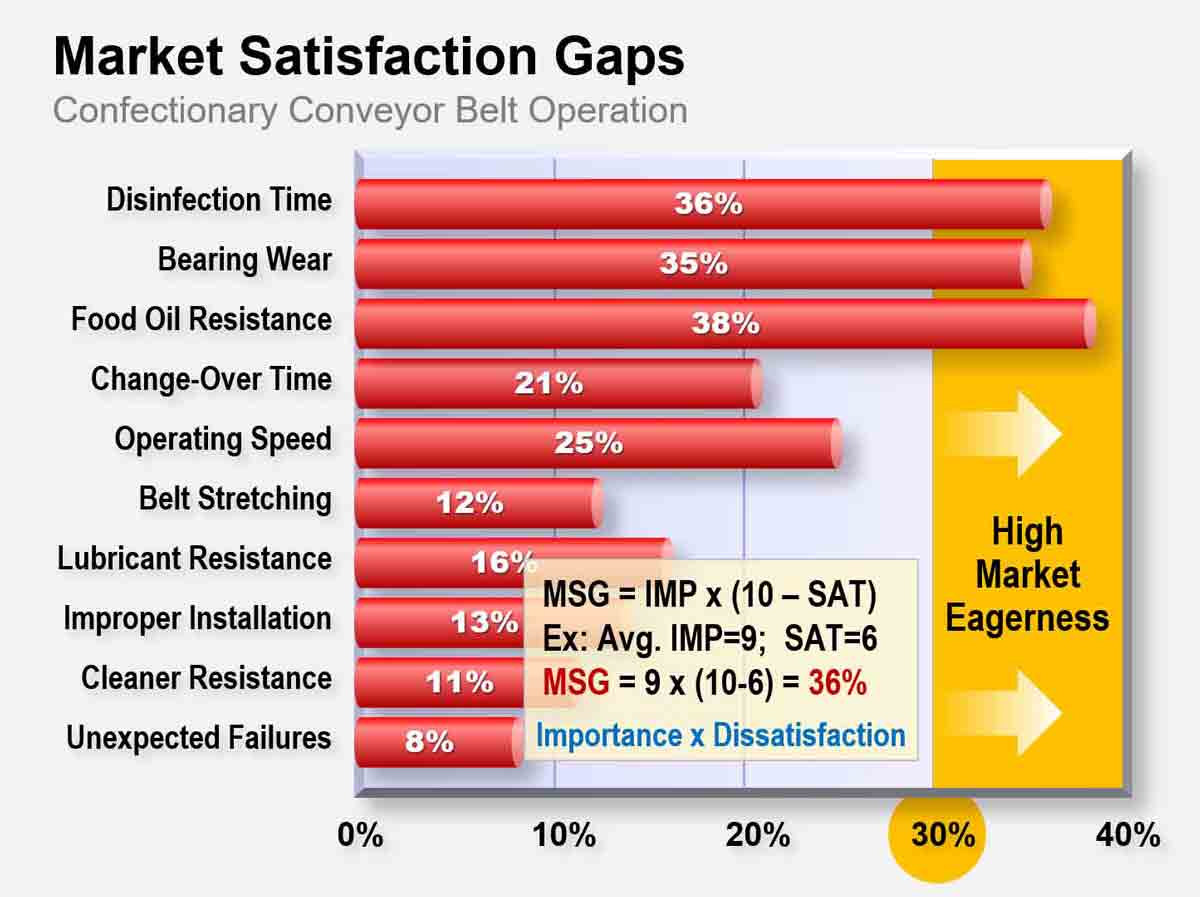

When you’ve completed Preference interviews for this market segment, you calculate a Market Satisfaction Gap (MSG) for each outcome: MSG = IMP x (10 – SAT). IMP is the average 1-to-10 importance rating for the market, and SAT is the average 1-to-10 satisfaction rating.

The more important and less satisfied customers are with an outcome, the higher the Gap. If a Gap is about 30% or higher, it tells you customers are eager for improvement. In our example, this includes Disinfection Time, Bearing Wear, and Food Oil Resistance. (See Market Satisfaction Gaps white paper and a dozen Case Stories for more.)

Market Satisfaction Gaps put “Define” Step 2 on steroids. Most practitioners of the design thinking process can’t even imagine this level of precision and confidence. In our experience, this quantitative work is the single most critical step a B2B company can take to boost innovation success.

Market Satisfaction Gaps put “Define” Step 2 on steroids.

When companies skip this quantitative step, serious problems arise. To understand this better, we benchmarked 50 new product development teams from 20 companies that had conducted 875 Discovery and Preference interviews.

An astounding five out of six teams (84%) said the impact of these interviews on their product design was “great” or “significant.” Without such interviews, five of six teams in most companies are likely working on the wrong design targets. Beyond this, here’s what the study teams said about these B2B-optimized interviews:

- 95% said they provided more insight than traditional voice-of-customer methods.

- 81% said they’d have a great or significant impact on project success if applied company-wide.

- 100% said they would have a positive impact on company-wide organic growth.

To summarize…

You can expect to hear more and more about design thinking processes. That’s wonderful news because design thinking starts with understanding customer needs. Strange as it might seem, this is something the vast majority of B2B companies still struggle with.

But don’t stop at adopting the same design thinking process used by everyone else. If you’re a B2B company, take advantage of your advantages and implement a B2B-optimized design thinking process. To learn more, check out these resources:

- www.reinventingvocforb2b.com An e-book explaining how voice-of-customer methods should be optimized for B2B.

- www.newproductblueprinting.com A four-minute video that describes the world’s leading B2B voice-of-customer methodology.

- www.blueprintingworkshop.com Monthly virtual public workshops where you can learn and even role-play B2B-optimized VOC.

Comments