The Voice of the Customer: A Primer for Everyone

“The Voice of the Customer”, an article by Abbie Griffin and John Hauser from 1993, joined the parallel worlds of academic market research with the practical discipline of new product development. As such, “The Voice of the Customer” built upon the leading framework at the time for building new products, QFD. (“QFD”, or “Quality Function Deployment”, was a product development method from the 1980s)

While QFD has fallen out of favor, the voice of the customer has not. Of course, modern practitioners still need a method to understand customer needs. And as it turns out, the basics of the voice of the customer are quite accessible for many. That is, the techniques can be learned by most anybody. Not just high-powered consultants or academics. But marketers, product managers, strategists and leaders who benefit from better customer understanding.

What is the voice of the customer?

The voice of the customer is a market research process for gathering and prioritizing customer needs. You could summarize the key purpose of the voice of the customer with the phrase to learn. Not just for the fun of learning, but for practical reasons. Though we’ll discuss the voice of the customer within the context of new product development, it’s useful in other areas. We all have customers and the better that we can understand their issues, the better we can create, market, and sell products that will be useful to them.

Two Phases of Market Research

There are two phases for the Voice of the Customer. The first is the qualitative phase, in which the purpose is to uncover a complete set of customer needs. The second is the quantitative phase, in which the purpose is to prioritize those same needs. This article is a primer for the qualitative phase in which the key method is the customer interview. “Qualitative”, meaning that we’re not using numbers or statistics for analysis.

This article is enough to get the beginner started. And yet, also a good review for the pros. Within this primer, we will discuss:

- Confirmation bias: enemy of the voice of the customer

- Preparation

- Conducting interviews

- Analyzing results

- Communicating results

These five steps each help us with the primary purpose of the voice of the customer, to learn,

Confirmation Bias: Enemy of the Voice of the Customer

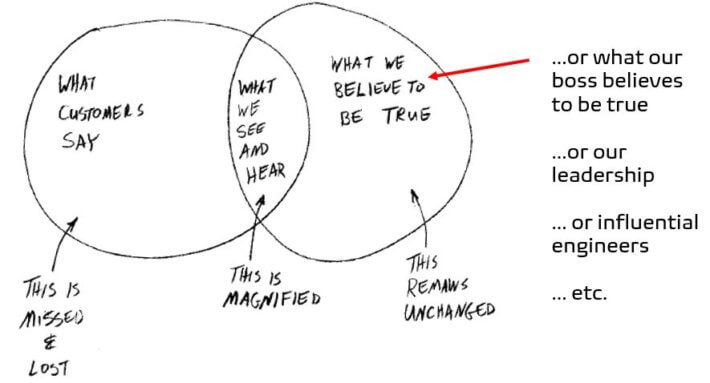

According to the American Psychological Association, “confirmation bias is the tendency to look for information that supports, rather than rejects, one’s preconceptions, typically by interpreting evidence to confirm existing beliefs while rejecting or ignoring any conflicting data.”

Let’s go deeper to understand the implications. Confirmation bias has the effect of making people magnify information that supports their currently held beliefs, values, and opinions. But it’s even worse than that. This human frailty can keep us from even hearing information that opposes our current positions. We don’t even hear the conflicting information.

Simply stated, we hear what we want to hear. We flush the rest.

Here are five techniques to address confirmation bias:

- Use a proven process for the voice of the customer

- Self-awareness

- Acknowledge your preconceptions

- Resolve to pursue the truth

- Expect this phenomenon in others

We begin with a proven process for the voice of the customer. Good process itself will steer us from trouble. Next, have a self-awareness of what confirmation bias is. You don’t need to be a psychologist, but just a general awareness of your vulnerability to magnify agreeable information.

Next, acknowledge your preconceptions. Especially when using the voice of the customer for product development, we often begin with a hypothesis of what the customer’s challenges are, and even what the product should be. These are not “evil thoughts,” and even likely are close to the truth. However, for purposes of gathering the voice of the customer, intentionally set these aside, at least until the customer insight project is over.

Learn the Voice of the Customer in an upcoming course from The AIM Institute

Armed with this self-knowledge, resolve to pursue the truth. Just make a decision that it’s best to learn the truth, regardless of your prior position. And finally, expect others to struggle to see things accurately from their own confirmation bias. You likely know something of their ideas, and so don’t be surprised when they tout how the voice of the customer is conveniently proving them to be correct.

Preparation for the Voice of the Customer

Establish objectives

Great preparation goes a long way. As you begin, work with your team to establish objectives. What are your goals? How will customer insight be helpful? What are the lingering questions that are slowing down marketing or development? And more specifically, what are you seeking to do? Is the larger initiative about developing new products? Updating current ones? Is it about developing marketing strategies? Pricing strategies? Selling strategies?

By the way, it’s often the case that we just want to generally explore a market. In which case, we may not have such a tangible objective as “update a current product.” That’s perfectly acceptable! In this case, our project is about uncovering the “unknown unknowns” just as Donald Rumsfeld once spoke of. It’s fine, but let’s just be clear on this point.

Build a sample plan

Simply put, a sample plan is our strategy for how many and what type of customers are we planning to interview. A good plan helps us to learn as much as possible from as few interviews as possible. Properly structured, a sample plan will make sure that we’ve included relevant diversity into our project.

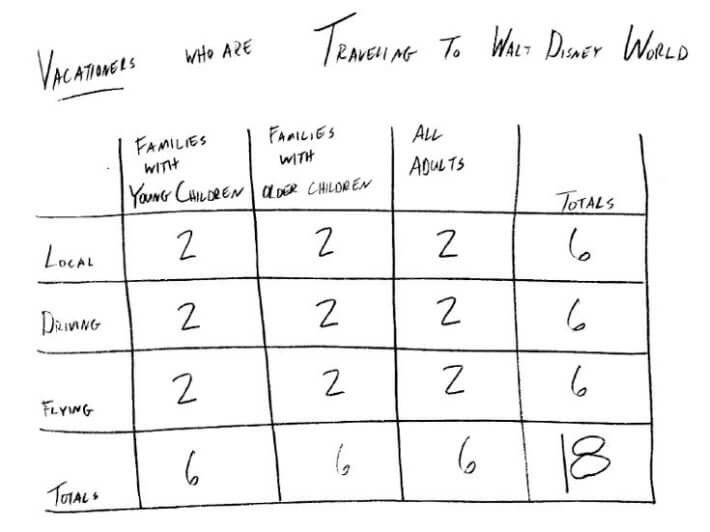

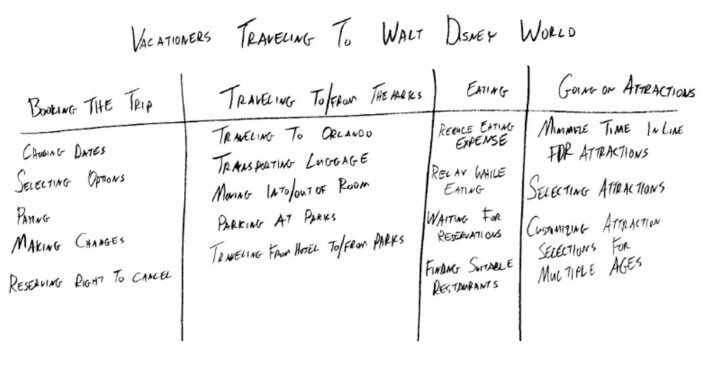

Consider a practical example. Imagine that you’re studying the market of vacationers who are traveling to Walt Disney World. To get started, consider what variables could cause customers to have different needs. Perhaps one might be the mode of travel to Orlando, FL. You might organize these into buckets of 1) local, 2) not local, but driving and 3) driving. Meanwhile, another variable might be group composition. You could have buckets of 1) families with young children, 2) families with older children, and 3) all adult parties.

Organize these into a matrix, with quotas as follows:

Write questions

The voice of the customer is revealed through an interview. The chief tool of the interviewer is the question. And questions are funny things. When asked, they create tension. Tension that isn’t resolved until answered. Let’s consider three general types: rapport-building, objectives, and wrap-up.

Rapport-Building

First, we have rapport-building questions. Within New Product Blueprinting, we call these “Current State” questions. For these, we’ll keep tension low. We’re more concerned about making the customer comfortable than learning per se.

Objectives

Second, we have objectives questions. These relate directly to the objectives for the voice of the customer initiative. We established these initially and should refer to them here. Take care to order your objectives questions from the least aided, to the most aided. Keep them as open-ended at first, and you can progressively provide hints. Within Blueprinting, the objectives questions are within the Problems, Ideal State, and Triggered Ideas section of the agenda.

Wrap-up

Finally, we have wrap-up questions. These are simply transitions at the conclusion of an interview, signaling that the session is coming to a close. These should again be light and easy. Since New Product Blueprinting is a B2B-optimized process, the wrap-up section consists of asking the customer to confirm what were the most important ideas that were presented. And finally, they are offered a PDF copy of the interview notes.

Select interview contexts

The best context for the voice of the customer is in their environment. The one in which they interact with the product in question, or are trying to accomplish the job-to-be-done of interest.

Therefore, if we’re to study vacationers who are going to Walt Disney World, the ideal is that we’re right there with them. Interviewing them and observing them while on their vacation. Obviously, this has some drawbacks. More costly. More time-consuming. And not that desired by the customers. But make no mistake, we’ll learn more in this context than any other.

The opposite side of the voice of the customer context is the web conference (or phone) interview. These are fast and cheap. Multiple could be done per day. But also, not as effective.

In-between, we’d have what we often think of as an interview for the voice of the customer. Sitting across a table talking. Perhaps as part of a focus group.

When executing the voice of the customer, there’s no “right” answer. Select the context that best fits your schedule and budget. However, with many projects, a mix of contexts often hits the mark, providing high-quality insight affordably.

Conducting Interviews for the Voice of the Customer

When conducting interviews for the voice of the customer, there are five keys to success: 1) Embrace the proper mentality, 2) Use distinct roles, 3) Probe for understanding, 4) Take excellent notes and 5) Debrief immediately after the session.

Embrace the proper mentality

To learn from our customers, it would be quite convenient if they had a USB input to their brain, from which we could download their needs. This not being the case, we, the members of interviewing team, must be the instrument of measurement.

Therefore, prior to a session, you’ll want to consciously quiet your brain. For this short session, don’t think about anything else other than your customer. If it helps, you might even consider breathing exercises or even listen to music. It’s important to drop everything mentally except for an extreme focus on your customer.

A Guided Conversation

As you conduct the “interview”, think of this as more of a guided conversation. This isn’t the TV show 60 Minutes. From the outside, it should appear as a conversation… just one in which one party (you and your team) just happen to be quite interested in the other’s problems.

Speaking of which, in your conversation with the customer, search for problems more than things that are going well. We ultimately innovate by addressing problems, and therefore, can learn more from things that make customers unhappy than we can from things that make them happy.

Finally, there will be no selling or solving during this conversation. A selling dynamic destroys the free sharing of honest information. Further, when we solve problems, we both waste precious time while unproductively biasing the conversation.

Use Distinct Roles

Each person on your interview team will have one of four distinct roles. These are Moderator, Note-taker, Observer, and A-V person.

The Moderator

The Moderator is the person who conducts the interview. They watch the agenda, follow the discussion guide and watch the time. The Moderator should do the vast majority of the probing. And importantly, the Moderator is the only person that should take the customer to a new topic.

The Note-taker

The Note-taker, not surprisingly, takes notes. Further, they should think of themselves as the historian of the team. Capturing everything possible. After all, the goal of the interview was to learn. Therefore, it’s critical that they capture the customer’s thoughts.

The Observer

The Observer is an optional role. However, they can greatly improve the effectiveness of a session. Of course, the Observer carefully listens to the customer. But they will reference the customer’s statements with both the notes that are taken and the probing of the moderator. The Observer is looking for what gets missed. The probing opportunities not taken. The notes not captured.

The A-V person

The A-V person is also an optional role. Moreover, this one is really needed more when doing contextual or ethnographic interviews. Their role is similar to the Note-taker. But instead of capturing the interview with words, they capture it with audio and/or video.

Throughout the interview, it’s critical that all defer to the Moderator. Otherwise, if the interviewing team members are wrestling for control of the session, it’s frustrating to the customer. This limits what the team will learn. Also, as the Moderator is probing, the destination of the questions may not be apparent to the rest of the team. Therefore, when they ask their own question in the middle, the thought is interrupted. While it’s acceptable for the rest of the team to ask an occasional clarifying question if, in doubt, it’s best to let the Moderator do the probing.

Probe for Understanding

The most curious Moderators will ask the best probing questions. We will never know exactly where a customer may go, or what they may say. If the Moderator will embrace their curious spirit, they will likely know what to ask. And quite frankly, if they are not curious about the customer’s concerns, they are probably in the wrong role.

One practical tip for probing would be to repeat the customer’s thoughts back to them but as a question. For example, imagine this dialogue with our Disney World vacationers:

Moderator: What challenges do you have when traveling to Walt Disney World?

Customer: It’s hard to find healthy food in the parks.

Moderator: It’s hard to find healthy food in the parks?

Just repeating their words back to them, as a question, invites them to elaborate in a way that reveals no bias while also showing respect for their own words.

How far to probe?

Further, you’ll find yourself wondering, “How much should we probe?” For this, just imagine that after the interview, you are going to immediately move to create ideas to address the problem. Do you understand it well enough to solve it? If not, keep probing.

Quite practically speaking, here’s a probe that works approximately 100% of the time: “Can you tell me a little more about that?” The skillful moderator should keep that one in their back pocket.

Know where the customer is a reliable (and unreliable) source of information

When uncovering the voice of the customer, it’s important to know how reliable they are. And this assessment will change based on the type of information they’re providing. When we ask the customer a question, we’re going to get an answer. But the problem is, there’s some information that customers are great at telling us -making them reliable sources – and other information types they are bad at telling us – making them unreliable sources. We must be able to distinguish these.

The following distinctions are from the book, The Statue in the Stone: Decoding Customer Motivation with the 48 Laws of Jobs-to-be-Done, W. Scott Burleson (2020).

Customers are reliable sources about: 1) What they seek to accomplish, 2) Any issues they are concerned about, and 3) Anything they have experienced.

Reliable source about what they seek to accomplish

Customers, and all people, know their jobs-to-be-done. They know what their objectives are. Their goals. They know what they are trying to do. When gathering the voice of the customer, they are the expert as to their objectives.

Reliable source about any issues they are concerned about

Customers are aware of what challenges are of concern. They know what errors, fears, and struggles worry them.

Reliable source about anything they have experienced

Of course, as people, we have limitations of memory – and even of how trustworthy our perceptions are. So clearly, “reliable” is a relative term. However, it’s indisputable that someone who has experienced something (traveled to Disney World) is a more reliable source about the challenges than someone who has not.

Unreliable source about what solution best suits their needs

Of course, we have the famous quote from Henry Ford, “If I’d asked my customers what they wanted, they’d have said a faster horse.” This illustrates the fallacy. Customers are experts in their problems, not in the solutions to those problems. Therefore, when a customer tells us what product or service they want, we shouldn’t take that idea too literally. This is a basic principle when seeking the voice of the customer.

Learn the Voice of the Customer in an upcoming course from The AIM Institute

What do we do when a customer requests a product or feature?

This isn’t a situation to fear. In fact, it presents perhaps the easiest opportunity for probing. In essence, we want to learn why the customer thought this product idea would help them. If the customer asks for a faster horse, we respond with something akin to the following:

- How would that help?

- What would that help you to accomplish?

- Why would you want that?

Notice that with these questions for the voice of the customer, we’re moving from something where the customer is unreliable (their requested product) to where they are reliable (what they seek to accomplish – or – any issues/concerns they are concerned about.

Unreliable source about where a product is over-performing

How can you tell if your internet speed is too fast? You can’t. You have no idea at which point the internet speed past a threshold beyond which you could detect. Notice that there’s a commonality at hand discussed in the “interviewing mentality” section above. This is the reason that during probing, it’s more useful to focus on problems rather than things that are going well.

Unreliable source Anything they’re not interested in

When gathering the voice of the customer, we’re going to have a hard time learning anything outside of the customer’s interest. However, if the sample plan is designed well, this shouldn’t be an issue.

Probe into the meaning of vague words

When seeking to understand the voice of the customer, we cannot be contented with vague customer needs. For example, here are some of the typical culprits:

- Easy to use

- Durable

- Reliable

- Simple

- Flexible

- Comfortable

Vague words such as these create the illusion of clarity. After all, when the customer said they want their product to be “easy to use”, they knew exactly what they meant. However, if our note-taker writes down “easy to use” as the customer need, and we leave it there, we haven’t truly captured the voice of the customer. Instead, we just have a vague phrase that, like art, will take a different meaning within the minds of those who gaze upon it.

Addressing vague words

Here’s the good news. When customers offer these nebulous terms, we’ll know exactly how to probe. Just ask them to define the opposite. For example, if a customer says, “I want my new product to be easy to use.” Then you reply, “What makes it difficult to use?” If they say, “This process should be simpler,” then reply, “What is currently making it complicated?” For our Disney World travelers, if they say, “I’d like for my vacation arrangements to be more flexible,” then reply with, “What would make them inflexible?”

Hopefully, you are starting to see some commonalities for understanding the voice of the customer. And it’s not enough to capture what the customer believes to be correct, we must also capture it so that it’s unambiguous. So that it will be correctly interpreted later.

Ladder Up and Down

When probing more deeply for the voice of the customer, “laddering” is the process of zooming out and seeing an issue in context. We “ladder up” to understand the implications of a problem. We “ladder down” to understand the root causes of a problem.

Ladder up to understand the implications

For example, within our Walt Disney World example, imagine that our customer replies that “It takes a long time to find a parking space.” Our moderator could begin by laddering up. It sounds like this, “How does this impact you?”, or, “Why is this a problem?” Perhaps the customer replies, “This means that I have to spend more time in transit, as opposed to just enjoying the parks.” As the moderator, you could ladder up again, “And how does that impact you?” The customer might reply, “It becomes frustrating, knowing that I’m not getting as good of a value.”

The more that you ladder up, the more that you’ll approach emotional, rather than functional needs.

Ladder down to understand the root causes

A key reason to seek the voice of the customer is to create new products and services. New offerings that solve customer problems. To solve them, we first need to understand the root causes. To understand the sub-problem that creates the larger one. When presented with the same statement, “It takes a long time to find a parking space,” laddering down sounds like:

- What contributes to this?

- Could you describe some of the root causes?

- What factors make this worse?

To this, the customer might say any of the following:

- The parking lots are so large. You spend a lot of time searching for that rare open spot.

- Most people arrive at the parks at the same time.

- Parking attendants are sometimes missing.

- My children are excited and loud, making it difficult to focus.

If we’re to solve a problem as presented by the voice of the customer, we have to understand the sub-problem. Our solution for missing parking attendants would be quite different than one to help with many arriving at the same time, or excited children.

Take excellent notes

It should be obvious that when documenting the voice of the customer, we need confidence in the notes. Churchill quipped that “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it.”

Let’s recall how this primer on the voice of the customer began, with a warning about confirmation bias. This is the force that acts as a filter. So that we magnify bits that we believe to be true, and diminish bits that we disagree with.

Therefore, it’s critical that our note-taker begins with a hyper-awareness of this tendency. But additionally, here are a couple of other strategies to ensure that we can trust the notes from our project seeking the voice of the customer.

Importance of verbatim notes

First, the note-taker should capture verbatim comments as much as possible. We can’t get into too much trouble when writing the exact words and phrases. However, when the note-taker stops, listens, and summarizes… you can bet that they’ve added their interpretation of the story.

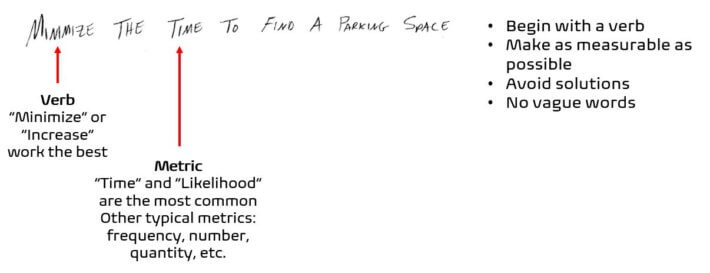

Next, as part of the voice of the customer project, use Anthony Ulwick’s ODI method to craft Desired Outcomes. (For a thorough treatment of this idea, read the classic innovation book What Customers Want.) Ulwick’s ODI (Outcome-Driven Innovation) provides a template for a customer need, in the form of a desired outcome. It begins with a verb (usually minimize), has a metric and a contextual clarifier. For example, if our Disney travelers complain about it taking a long time to find a parking space, we might convert that to an outcome statement such as, “Minimize the time to find a parking space.”

It does take time and practice to be able to create desired outcome statements well. However, it’s worth the effort. You end up with something unambiguous and stable that accurately reflects the voice of the customer. These statements can then be easily used within a survey or similar prioritization methods.

Debrief Immediately

Every principle for understanding the voice of the customer ultimately is to address the same objective, to learn. To that end, after conducting your interview, it’s critical to debrief immediately.

It’s tempting to omit this step. To instead, make arrangements to get together in a few days to go over the notes. However, know that if you wait even a single day, you’ll have forgotten much of what you heard. This article from AIM’s own BlueHelp™ resource presents the Ebbinghaus forgetting curve, which shows that people forget about 50% of what they learn within a day. However, if they’ll recall and review within 24 hours, this “forgetting” can be as little as 20%.

Additionally, the voice of the customer is a multi-player activity. Nearly all the time, the interview will be conducted by a team of 2-4 people, perhaps more. Therefore, when reviewing immediately after the actual interview, between all the team members, it’s unlikely that anything would be missed or forgotten.

What do you do during the Debrief?

During the debrief, you’ll review notes – both the “official” ones as well as those of the observer and moderator. The team will discuss themes, both within the feedback from this interview as well as others. The voice of the customer is not so much extracted from a single individual as it is the collective song from many interviews. Across the scope of your project, the patterns will emerge.

Analyzing Results for the Voice of the Customer

The primary purpose of the qualitative phase is to uncover a list of customer needs (aka “Desired Outcomes). If doing so, and we have a great list of Desired Outcomes, we’re ready to proceed with prioritization within a quantitative phase. That usually means that we’ll employ a survey with a high sample of customers. But not always.

Even within this qual phase, the Voice of the Customer can be heard. That is, we can still find actionable results. Many innovations have been developed using qualitative data alone.

But to do so, without the power of statistics, we must be quite intentional about our work. First, we’ll maintain as much objectivity as possible. To do so, elevate any conclusions that seem contrary to conventional wisdom. Or at least, to the wisdom of the interview team. Take on the persona of a contrarian.

Also, involve others with the interpretation of the voice of the customer session notes. This will naturally keep any one person from forcing their interpretation to be “the” conclusion. Next, compare the results to previous studies. What’s consistent? What’s different? After all, all studies seeking to understand the voice of the customer will have biases and weaknesses. A meta-analysis of many will help to average these out. This will help to triangulate to the truth.

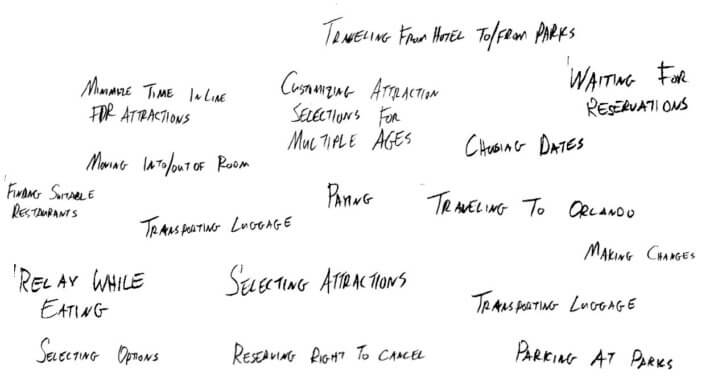

Affinitize

When you affinitize, you look through all the various Desired Outcomes in order to group them logically. If doing a survey later, these groupings will be natural sections for the survey. But even if not, they will help themes to emerge. It’s just a way of making sense of lots of information… trying to understand what is within.

Also, the nice thing about an affinity exercise, is that your team can more or less mechanically proceed to organize the outcomes. It’s a way of letting the themes naturally emerge rather than forcing something.

Involve others

When doing so, make sure and involve others. It’s not a solo sport. There would be too much opportunity to influence the results. And even better, if possible, involve actual customers in this exercise. How do they see these needs? What themes do they see? Certainly, real customers will not be victims of the most common reason for bad analysis – the impact of current products, ideas, and technologies that a company has been working on already. It’s too tempting for engineers, product managers, leaders to see customer needs through the lens of what they’d like to hear.

One final thought on schemes for affinitization. Consider creating a job map. This is a process map of all the steps that a customer must complete. For more on this, watch this AIM video from the Master Class series.

Draw conclusions, present caveats

When seeking to understand the voice of the customer from a qualitative project, such as one driven by interviews, it’s difficult to present unbiased conclusions. There are two extremes. In the first, we exploit the weaknesses of a qual process as evidence to support our preconceptions, or, to forward along with any personal agenda. In the other extreme, we take on the role of market researcher-scientist and refuse to present any findings not supported by hard statistical analysis. Let’s avoid these extreme positions.

Present the caveats

Moreover, if we’ve been diligent about pursuing the truth, following good process, and proactively addressing confirmation bias, then we’ve earned the right to present our conclusions. But when doing so, let’s present the caveats. This was a qualitative effort. We have found evidence, but not proof. Present your evidence, and along with your team, state what you believe the conclusions to be.

You and your team will still be left with this question, “Do we have strong enough evidence for our conclusion, or, should we recommend that a follow-up quantitative phase will be needed to truly understand the voice of the customer?” If in doubt, there’s no disputing that the lowest risk path will, in fact, be to execute a subsequent quantitative phase. Most often, this involves a customer survey.

Communicating Results for the Voice of the Customer

Eventually, the time comes to present what you’ve learned. Time to share the voice of the customer with others. First, you’ll share the data. Second, you’ll share a narrative of your conclusions.

Share the data

For the data, begin by providing details about the sample. This part is easy, as you’ll just provide an updated sample plan. If appropriate, you could even add demographic/firmographic information while obviously, not sharing individual private information about individuals..

Provide the entire list of customer needs, hopefully, worded as Desired Outcomes. If more than 30, it would be a good idea to provide these in advance as handouts.

Emphasize that this was a qual study

There’s a lot of responsibility in presenting the findings from a qualitative study capturing the voice of the customer. To a great extent, you’re asking your audience to trust your judgment. And so, begin by stating this fact. That you and your team are doing your best to be impartial, but that this is a qualitative, not a quantitative study.

To that end, do not use numbers or percentages to support your case. For example, imagine that for our Disney World project, you only interviewed six customers. it would be poor practice to suggest that 16% had problems booking restaurants when actually, that just meant that a single customer had that problem.

Use AV to tell the story

Once you know the story you want to tell, let the customer tell it. At a minimum, share some verbatim customer comments that support the major themes. But even better, provide audio or video of customers describing these problems… or best of all, video of them actually experiencing the problem.

Using AV to tell the story is powerful. If we see a customer experiencing an issue, or see them experiencing it, this is powerful persuasion. Therefore, please use this power responsibly. You’re using the AV to clarify a conclusion that you came to within your analysis.

Common leadership challenges with the Voice of the Customer

When presenting to leadership, there are three common challenges. First, because they often like to move fast, they may miss the caveats about the limitations of qualitative work. Especially if the conclusions are in sync with their previous notions, they may be dismissive about proceeding forward with a survey. For this reason, you’ll want to repeatedly emphasize this point. Further, they will look to you for guidance on whether a quant phase is needed. State your opinion boldly, whichever position you have.

Good research often creates new questions

Next, leadership can fail to understand that research often presents new questions. This can be frustrating for them, as they may believe that something is amiss. How can good research create new questions? However, rest assured, this is normal. Additionally, it might even be a better idea to launch another qualitative VoC project to explore these new questions. Just do your best to explain this. You’ve been leading the project, and you will likely be the expert on what action should come next.

Plan for processing time

Finally, leadership often doesn’t understand the need to take time to process the voice of the customer results. Instead, they think that the project will finish on Tuesday, and product development can begin on Wednesday. It’s just not a good idea to force things like that. You must begin to mitigate this from the beginning. Set expectations that the broader team will need several weeks at a minimum to process what’s been learned.

The Voice of the Customer: A Primer for Everyone

The original article “The Voice of the Customer” was a significant event in the history of customer insight-driven innovation. In the years since thought-leaders continue to contribute to this field of knowledge.

Edward McQuarrie, with his book Customer Visits, gave practical logistics for qualitative research. Clayton Christensen added jobs-to-be-done. Tony Ulwick took that further with Outcome-Driven Innovation. Naomi Henderson perfected qualitative probing. And Dan Adams developed the only B2B-optimized customer insight process.

Going deeper…

If interested in going deeper within the Voice of the Customer, please reference the works of those authors above. However, the intention of this primer was to provide an actionable reference. Providing the basics that you need to get started. Beyond this primer, you might also consider formal training in a VoC process such as New Product Blueprinting. Even better, find some work colleagues who are also interested, and pursue the skills together. Just keep this final point in mind: like any skill, the only way to truly develop expertise is to actually practice.

And so, take a course, read a bit more, and execute your own project to uncover the voice of the customer! Your career will certainly benefit, as will your current and future employers.

Learn the Voice of the Customer in an upcoming course from The AIM Institute

Comments